Self-efficacy can be defined as a confidence or belief in one’s ability to achieve or make an impact (self-agency). What impact does self-efficacy and a student’s agency have on our classrooms? More than we think it does, and much more than our current school structures suggest.

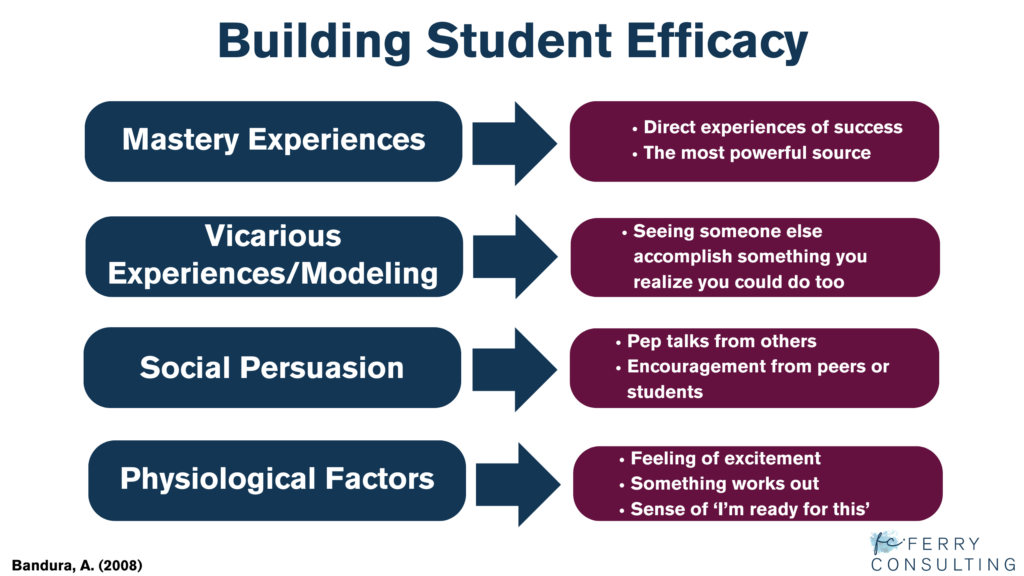

Bandura’s (2001, 2008) research related to student efficacy shifted our understanding of how we can impact student confidence in their abilities. Thanks to Bandura, and others, we know that student learning is significantly impacted by a student’s belief in their own achievement. To put simply, when a student in our classroom possesses the belief they can achieve in your classroom, they will. It would be great if it were that simple. However, there are 4 key strategies, identified initially by Bandura (2001) and later confirmed by other researchers, that effectively build a student’s efficacy.

Mastery Experiences

One of the key motivating factors for humans is mastery (Pink, 2009). When we feel masterful at something it leads to a feeling of success, a win, which leads to a feeling of wanting more success. When we want more success we are willing to take risks to stretch out of our comfort zone. When we move outside our comfort zone we can acquire new learning, which can lead to more masterful experiences. It is an identity positive cycle of mastery leading to increased confidence which leads to more mastery. What does this mean in the classroom? We have to create mastery experiences for students everyday in our classroom. Even small wins make an impact on student efficacy. The catch is that we have to encourage students to engage and risk failure to achieve those mastery experiences. We must create safety in our classroom cultures that encourage meaningful engagement from students. If students who lack confidence believe there is a risk of failure, they often won’t risk the engagement to reach for the win. Small, incremental steps towards successful experiences can make all the difference for risk-averse students.

Here are some suggestions to build those small wins.

- Encourage students to share a group response rather than an individual response to a question.

- Allow students to work in groups when critical thinking and problem solving is required.

- Ask open-ended questions with many ‘right’ answers to allow for multiple wins for multiple students.

- Ask students to engage in low-floor, high-ceiling tasks that allow for a range of entry points into the task.

Vicarious Mastery Experiences

There is something to the idea that if a peer or friend has a mastery experience it will impact other students. For example, if Zach (a student in your classroom) relates to Paul (another student in your classroom) and Paul has a successful experience in your classroom then Zach will think “I am like Paul, if he can get a win in the class then I can too”. Incorporate group activities into your classroom as much as possible. These related wins bring as much of a boost to student efficacy as if the student had the experience themselves. When we ask students to work independently on challenging tasks we can be setting them up for a negative experience. When a student doesn’t feel confident in your classroom and they are left to work independently they often won’t move outside their comfort zone to get the win. However, students are more likely to take a chance and try when they are with their peers and feel supported.

A few suggestions:

- Call out positive, mastery experiences in your classroom. You might say, “Lucy, I love how you were a risk-taker today when you made that creative suggestion for a first step”.

- Ask students to engage in group activities that are open ended, with multiple entry points and multiple ‘right’ answers.

- Celebrate the small wins in your classroom where other students can hear and see the mastery accomplished by other students.

Pep Talks

Never underestimate the power of a pep talk! Bandura (2001) describes how simple words of encouragement can make a significant impact for students. When we set students up for small wins in the classroom combined with words of encouragement that are intentional and authentic, we create opportunities to build student efficacy. I would encourage you to be specific in your encouragement rather than something like, ‘great job’. Include the student’s name in the praise and shout out.

Some suggestions:

- Provide authentic feedback for a job well done that specifically aligns to what is meaningful to the student. Know your students’ interests and beliefs about themselves. As a student, if I don’t believe I am a ‘math person’ (there is no such thing), then praise specifically addressed to that belief can be meaningful.

- Words of encouragement expressed with emotion and pride have more impact.

- Be specific in your praise. For example, “Zander, your effort and perseverance in that last task was extraordinary. I loved how you hung in there and encouraged your group.”

- Words of encouragement do not always have to be related to content!

Cheerleading

Bring a level of excitement to the classroom and be a cheerleader for your students. When your students feel the excitement and energy you bring to their success, they will seek out that success for themselves. If you aren’t someone with a high energy level, fake it! We know that excitement and positive energy breeds more positive energy, so play it up.

As we consider these 4 strategies that positively impact student efficacy and agency, we want to reflect on how we can truly embed them into our everyday classroom experiences. Our words and actions significantly impact students’ beliefs. Be a positive influence on those beliefs by being intentional in planning your content to include these 4 strategies.

Research Basis

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1-26.

Bandura, A. (2008). An agentic perspective on positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Praeger perspectives. Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people (Vol. 1., pp. 167–196). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Pastorelli, C., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Rola, J., Rozsa, S., & Bandura, A. (2001). The structure of children’s perceived self-efficacy: A cross-national study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 87.

Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.